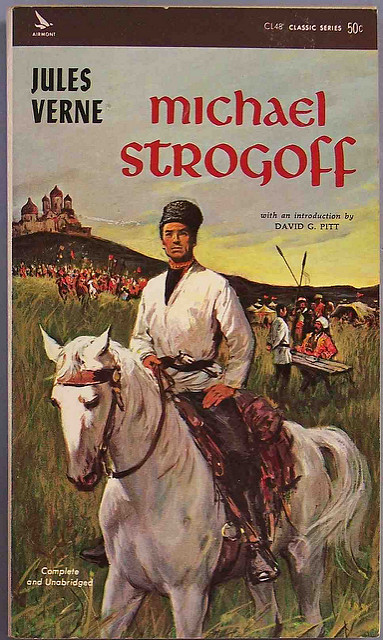

Michael Strogoff by Jules Verne is a 19th century adventure novel. It’s less well-known than Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea or A Journey to the Center of the Earth, but I liked it better. I don’t remember much about those novels.

Michael Strogoff is a special courier for the Czar. The Tartar hordes are invading Siberia, and the Czar needs to get a message to Irkutsk warning of a traitor plotting to sabotage that city’s defenses.

Michael Strogoff would be a typical adventure, with its prerequisite, larger-than-life hero, except for two characteristics. First, it made me root for a Czar and his military forces. I’m no expert on Russia, but I have a notion Czars where not the most sympathetic characters. Nor does the image of Cossack cavalry inspire me with warm fuzzies.

Second, Michael Strogoff is not your typical action hero. In my youth I read 24 Tarzan novels, and I don’t recall Tarzan ever shedding a tear. Mr. Verne never comes right out and admits Michael was crying, but there was clearly something in his eye when he was under duress at the hands of his enemies.

Here’s the situation: the Tartars have captured Michael and his mother. They might decide to do some bad stuff to his mom at any moment. Meanwhile, they are going to make Michael go blind, which, I guess, is what Tartars do sometimes. They pass a red-hot blade before Michael’s eyes, in the Tartar custom of blinding prisoners.

In the tradition of bad guys everywhere, the Tartars grossly underestimate the hero and eventually let him go (because he’s helpless, right?). The blinded Michael, and some girl he hooks up with, struggle across the steppe just in time to save Irkutsk. There, Michael kills the traitor in a sword fight. That’s right, a sword fight. How is blind Michael able to do this? Guess what? Michael’s not blind! He never was.

Everybody (except the reader) is shocked to discover this. Even his girlfriend, who led him across versts and versts (old Russian kilometers) of countryside, was hoodwinked by his blindness scam. It’s anybody’s guess why he couldn’t let her know, in a private moment, he wasn’t really blind. Maybe he was using her pity to coax back rubs out of her.

Anyway, here is the inspirational reason Michael was able to escape being blinded by the hot blade passed over his eyes: he was crying at the time. Mr. Verne doesn’t use the word crying; that might be unbecoming a classic hero. Michael was upset with worry about what the Tartars might do to his mom (they ended up letting her run free too) and there was just a little layer of water covering his eyes when the hot blade passed by. This little bit of water insulated his optic nerves from the heat, or something like that. Consult Dr. Verne for the technical explanation.

This series of events is a great comfort to me, because if Tartars ever come after me with a red-hot blade, I guarantee, even lacking endangered relatives, I will be bawling my eyes out. My optic nerves will remain cool and calm under my pool of tears. I just have to make sure to walk into some stuff afterward so they’ll think the procedure a success and let me go.

Even if he didn’t cry us a river, Michael certainly got teary-eyed. I’d have preferred it if he saved his vision through some more clever means, and then, after wreaking his terrible wrath upon the Tartars, took a moment to get misty-eyed about his poor mama. I don’t mind heroes having a sensitive side, but I don’t like them to cry their way out of trouble; toddlers shouldn’t even be allowed to do that. I want great heroes of literature to hold their tears until some serious bad-guy ass has been kicked. Is that too much to ask?

I shouldn’t make too much of the crying. I did enjoy the adventure. Besides, if shedding a few tears would have helped me defend Irkutsk, when I played Risk as a boy, I would have let them flow in a heartbeat.