My wife is my initial beta reader. Like me, and in a strange coincidence, she also has three young children. Together with her many jobs and responsibilities, these children make it as difficult for her to find time to read as they make it for me to find time to write – probably more so. Consequently, I must be patient and find something else to work on while awaiting the initial feedback on the latest work.

Lacking a suitable idea for a new project, I am left with the daunting notion of revisiting some old projects. I have four unpublished novels in completed draft form. That is to say there are four that come to mind; there may be others my subconscious finds too painful to contemplate.

Of the four, one can probably be fixed to meet my standards for publication. Another might have potential, but needs serious structural work. The other two are long shots. All four need lots of attention.

It’s difficult to get motivated to do the amount of rewriting that even the best of them would require. Rewriting doesn’t touch the good and the fun parts very much. The peaks are fine; it’s the dark, grimy, stinky valleys that beg rewrites. Your brain gets dirty and sweaty at the very bottom of the pit.

I know I eventually have to put on my overalls and get down into the dirt of the salvageable novel, but I’ll still find excuses to put it off. As for the others, I may just save those for when I’m famous, and also dead.

The After I’m Dead (AID) novels will be my last embarrassing legacy. My money-grubbing great-grandchildren will bring them to light for a quick payday. People will shake their heads at the poor quality, but do so quietly out of respect for the departed. Since I will be famous (play along with me) and also dead (couldn’t have happened to a nicer guy), morbid curiosity will turn these into my best-selling books.

-“And now, sweet grandchildren, you must promise that you will never bring this sub-par manuscript to light.”

-“We won’t. We swear on our grandfather’s grave.”

My great-grandchildren will buy 10,000 square-foot homes in Malibu and I’ll roll over in my 12 square-foot grave.

Perhaps I should really get to work on rewriting the AID novels after all. I like to keep still when I’m sleeping.

I guess I should start with the salvageable novel first, because nobody gets to live in Malibu if I don’t get famous before I croak. On the other hand, I don’t want to live in Malibu and, at this rate, my great-grandchildren don’t deserve to.

So maybe I’ll just keep procrastinating. Maybe I’ll even write some more meandering blog posts as an excuse to avoid the hard work waiting for me.

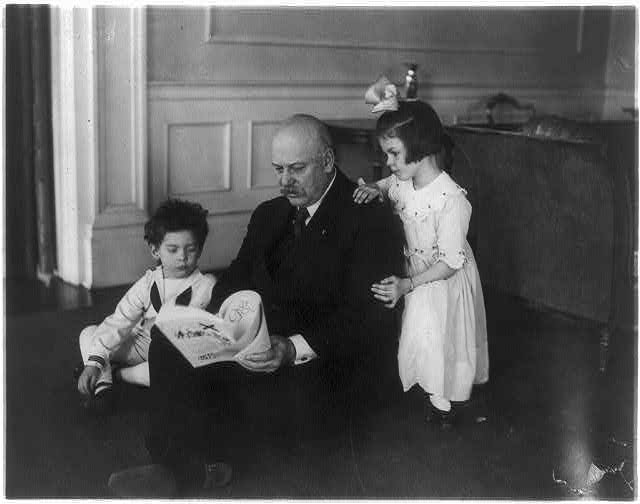

Maybe I’ll spend the time with my kids, teaching them lessens they can pass on to their children and grandchildren about how not to be mooching, greedy bastards.

Who knows what I’ll do. At any rate, I most likely won’t become famous.

That’ll teach ‘em.