A funny thing happened while I was Googling myself. What, you don’t Google yourself? Whatever. I’m not ashamed to admit it. I keep track of myself online, because well, really, who else is going to do it?

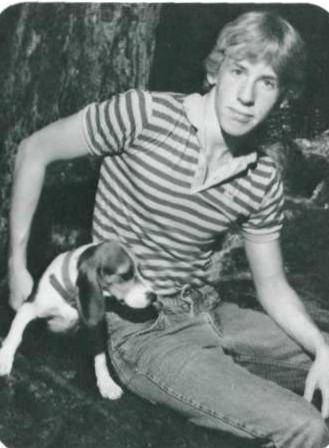

Anyway, the results were pretty standard stuff: links to my blogs, links to my books on Amazon, the web site that will tell you everything you ever wanted to know about me (or a guy with a very similar name) for a small fee, and a link to my senior picture in the 1985 St. Johnsville Central High Yearbook.

There was a link to Berkeley Fiction Review (BFR). They published one of my stories about 10 years ago, so that made sense.

Then there was a link to the BFR Wikipedia page. Why, I wondered, would a search of my name bring up BFR on Wikipedia? I clicked it.

I scanned the page of information about the whys and wherefores of Berkeley Fiction Review. There, in the middle of the page, was my name, listed with about 40 others under the heading, “Notable contributors.” I am on the same list as Charles Bukowski. I confess, I don’t recognize most of the other names on the list, but they must be of some minor renown, as the majority of them have links to their own Wikipedia pages.

I don’t have my own Wikipedia page, but at the rate I’m going, I figure if I keep Googling myself, one will eventually show up for my troubles. And then I’ll be “big time.”

I understand users are allowed to edit Wikipedia entries, but I promise I had nothing to do with putting my name down as a notable contributor. For one thing, I’d be too afraid of crashing the entire Wikipedia empire to attempt making an edit.

Worse, what if they had a way to trace it and found out I was the one who put my own name on a list of nearly famous writers? That’d be awkward.

I don’t know how I got on the list of “Notable contributors,” but I sure am tickled to be there. I thought about adding a signature line to emails I send that says: “Scott Nagele, Notable contributor,” but then a wave of humility (perhaps it was envy) swept over me. After all, I was one of the minority whose name showed in plain, black font, not one of the specials in the inviting, blue, “link to my personal Wikipedia page” font. My static, disconnected name leads nowhere.

Still, among the many hundreds of BFR contributors over the years who are not notable enough to merit their own Wikipedia entries, I must be among the 20 most notable. Either that, or somebody just picked a few random names from a past issue in order to fill the holes in the list of blue-fonters. Either way, I’m mentioned on Wikipedia. So how ‘bout them apples?