These are probably the cold feet I should have had before my wedding. But I was fairly secure in what I was getting into that day. I was more worried about something embarrassing happening at the ceremony than any of the ever after part.

The cold feet I avoided at my wedding have come to me over a book. This month, I will be releasing my third self-published book, A Housefly in Autumn. You’d think I would worry less about my third than my first two, but I don’t. I worry more.

Why doesn’t it get easier? It probably would get easier if I could stick to one genre. If I wrote the same kind of book every time and knew what to expect from the audience of that single genre, I’d likely feel more comfortable. But I’m trying something different. This is the first non-humor novel I’ve published. It’s not the first one I’ve written, but nothing hits the fan until you publish.

One of the benefits of self-publishing is you get to take risks. Nobody in a corner office is going to stop you from pissing away the firm’s money, because there is no firm, and more to the point, there is no money. It’s only your own blood, sweat, and tears you are potentially pissing away, and you can make more soon enough. Even so, risk can be daunting when it has your name attached to it.

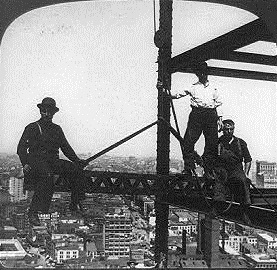

Some early self-publishers enjoying the freedom to take risks. Or maybe they’re just some guys building a corporate corner office.

Switching genres is a risk. The bigger risk is living between genres. This new book falls somewhere between Young Adult and General Fiction. Some books have succeeded very well in this gray area. Many more have failed.

There are some other little risks built into the story and the telling of it, but the little risks wouldn’t be extraordinarily frightening if not coupled with aforementioned, larger risks. In combination, each little risk has the potential to break the camel’s back.

Still, any worthwhile undertaking should be daunting. There comes a time when you have to damn the torpedoes, in spite of the risk. Yeah, I’ll fret over the release of this book, because that’s the nature turning your art toward the public eye. But I will also find confidence in recalling how much time and hard work went into producing it. Time and hard work might not be enough to claim success, but it’s enough to take a shot at it.

I’m taking this shot, regardless of my slightly chilly feet. My feet and I will do our best to make a success of this book while brewing up some new blood, sweat, and tears for the next one, which will be of yet another new genre. I guess it’s a good thing I don’t have any corner offices, or corporate money, to stop me from taking risks. All I’ve got is a pair of light blue feet, and having stood firm before the altar, they can stand behind a little old book.

Read more about A Housefly in Autumn here.